---

title: "How to standard deviation and variance in R"

date: 2026-02-20

categories: ["statistics", "standard deviation and variance"]

format:

html:

code-fold: false

code-tools: true

---

# Standard Deviation and Variance in R: A Complete Tutorial

## 1. Introduction

Standard deviation and variance are fundamental measures of variability or spread in data. They tell us how much individual data points deviate from the average (mean) value. While the mean tells us the central tendency, variance and standard deviation reveal how clustered or dispersed our data points are around that center.

**Variance** measures the average squared differences from the mean, while **standard deviation** is simply the square root of variance. Standard deviation is more interpretable because it's in the same units as our original data.

**When to use them:**

- Describing the spread of continuous numerical data

- Comparing variability between different groups or datasets

- Quality control and identifying outliers

- Risk assessment in finance

- Understanding measurement precision in experiments

**Key assumptions:**

- Data should be numerical (continuous or discrete)

- Works best with roughly normal distributions

- Sensitive to outliers

- Assumes data points are independent

These measures are essential building blocks for more advanced statistical concepts like confidence intervals, hypothesis testing, and standardized scores.

## 2. The Math

**Variance Formula:**

```

Variance = Sum of (each value - mean)² / (n - 1)

```

**Standard Deviation Formula:**

```

Standard Deviation = Square root of Variance

```

Where:

- **Each value** = individual data points in your dataset

- **Mean** = average of all values

- **n** = number of observations

- **n - 1** = degrees of freedom (used for sample variance)

**Why square the differences?** If we didn't square them, positive and negative deviations would cancel out, giving us zero. Squaring ensures all deviations are positive.

**Why divide by n-1?** This is called Bessel's correction. When calculating sample variance (which we usually do), dividing by n-1 instead of n gives us an unbiased estimate of the population variance.

## 3. R Implementation

Let's start by loading the necessary packages and exploring the penguin dataset:

```r

library(tidyverse)

library(palmerpenguins)

# Look at the structure of our data

glimpse(penguins)

```

```

Rows: 344

Columns: 8

$ species <fct> Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Ade…

$ island <fct> Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgers…

$ bill_length_mm <dbl> 39.1, 39.5, 40.3, NA, 36.7, 39.3, 38.9, 39.2, 34.…

$ bill_depth_mm <dbl> 18.7, 17.4, 18.0, NA, 19.3, 20.6, 17.8, 19.6, 18.…

$ flipper_length_mm <int> 181, 186, 195, NA, 193, 190, 181, 195, 193, 190, 1…

$ body_mass_g <int> 3750, 3800, 3250, NA, 3450, 3650, 3625, 4675, 3475…

$ sex <fct> male, female, female, NA, female, male, female, mal…

$ year <int> 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 20…

```

**Base R functions:**

```r

# Remove rows with missing values for cleaner analysis

penguins_clean <- penguins %>% drop_na()

# Calculate variance and standard deviation

var(penguins_clean$body_mass_g)

sd(penguins_clean$body_mass_g)

```

```

[1] 644988.4

[1] 803.1

```

**Using tidyverse for group calculations:**

```r

# Calculate by species

penguins_clean %>%

group_by(species) %>%

summarise(

mean_mass = mean(body_mass_g),

var_mass = var(body_mass_g),

sd_mass = sd(body_mass_g),

n = n()

)

```

```

# A tibble: 3 × 5

species mean_mass var_mass sd_mass n

<fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <int>

1 Adelie 3706. 250892. 501. 146

2 Chinstrap 3733. 218730. 468. 68

3 Gentoo 5092. 282579. 532. 119

```

## 4. Full Worked Example

Let's analyze the body mass variability of penguin species step by step:

```r

# Step 1: Prepare the data

penguins_mass <- penguins %>%

drop_na(body_mass_g) %>%

select(species, body_mass_g)

# Step 2: Calculate overall statistics

overall_stats <- penguins_mass %>%

summarise(

mean_mass = mean(body_mass_g),

variance = var(body_mass_g),

std_dev = sd(body_mass_g),

min_mass = min(body_mass_g),

max_mass = max(body_mass_g),

n = n()

)

print(overall_stats)

```

```

# A tibble: 1 × 6

mean_mass variance std_dev min_mass max_mass n

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <int> <int>

1 4207. 644988. 803. 2700 6300 333

```

```r

# Step 3: Calculate by species for comparison

species_stats <- penguins_mass %>%

group_by(species) %>%

summarise(

mean_mass = mean(body_mass_g),

variance = var(body_mass_g),

std_dev = sd(body_mass_g),

cv = sd(body_mass_g) / mean(body_mass_g) * 100, # Coefficient of variation

n = n()

) %>%

arrange(desc(mean_mass))

print(species_stats)

```

```

# A tibble: 3 × 6

species mean_mass variance std_dev cv n

<fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <int>

1 Gentoo 5092. 282579. 532. 10.4 119

2 Chinstrap 3733. 218730. 468. 12.5 68

3 Adelie 3706. 250892. 501. 13.5 146

```

**Interpretation:**

- **Gentoo penguins** are heaviest on average (5,092g) but have the lowest relative variability (10.4% CV)

- **Adelie penguins** have the highest relative variability (13.5% CV) despite similar average mass to Chinstraps

- The overall standard deviation (803g) is much larger than within-species standard deviations, indicating species is a major factor in body mass variation

## 5. Visualization

```{r}

#| label: setup-sd-data

#| echo: false

library(tidyverse)

library(palmerpenguins)

penguins_mass <- penguins %>%

drop_na(body_mass_g) %>%

select(species, body_mass_g)

species_stats <- penguins_mass %>%

group_by(species) %>%

summarise(

mean_mass = mean(body_mass_g),

variance = var(body_mass_g),

std_dev = sd(body_mass_g),

cv = sd(body_mass_g) / mean(body_mass_g) * 100,

n = n(),

.groups = "drop"

) %>%

arrange(desc(mean_mass))

```

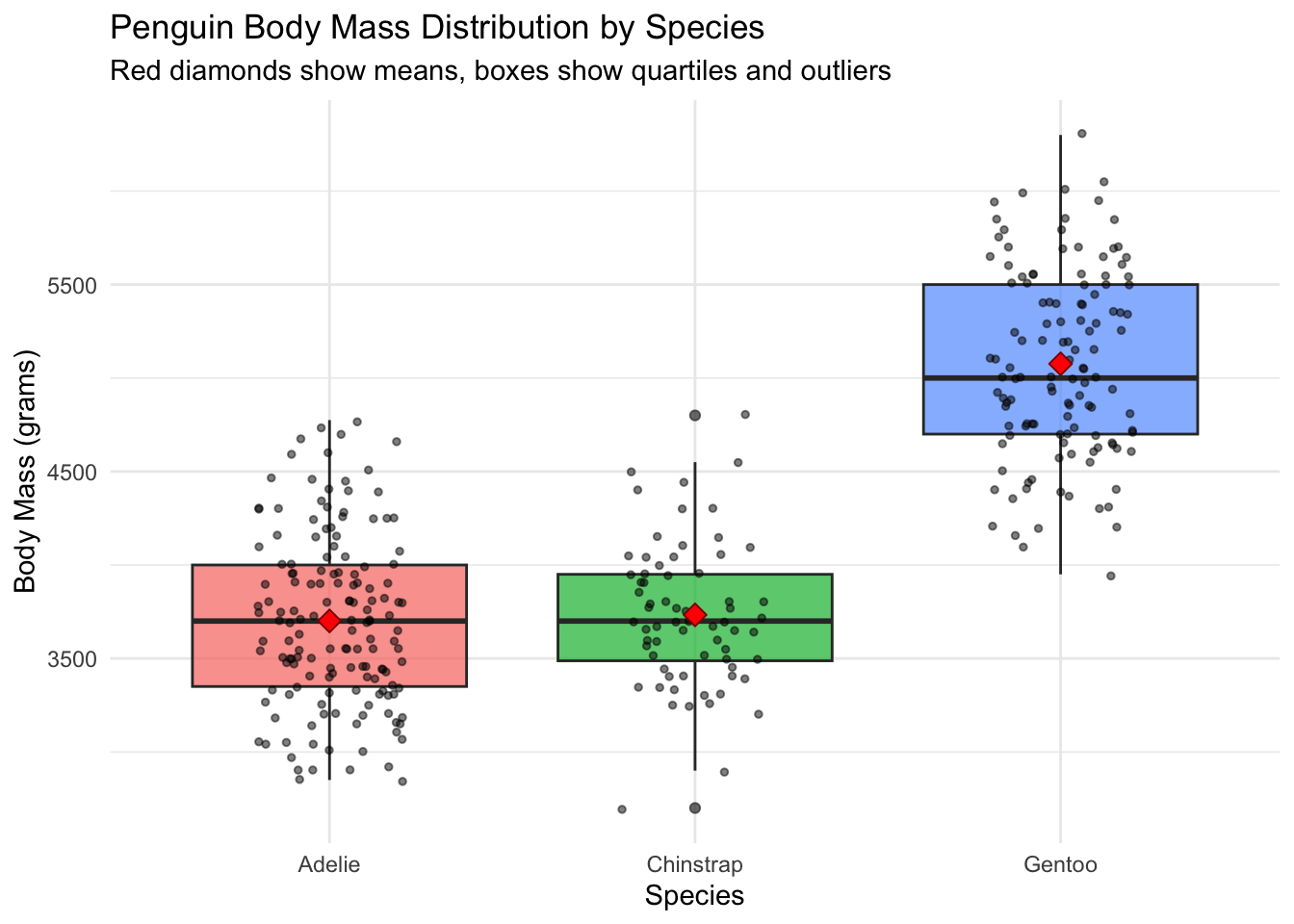

```{r}

#| label: fig-boxplot-species

#| fig-cap: "Penguin Body Mass Distribution by Species"

# Create a visualization showing distributions and variability

penguins_mass %>%

ggplot(aes(x = species, y = body_mass_g, fill = species)) +

geom_boxplot(alpha = 0.7) +

geom_jitter(width = 0.2, alpha = 0.5, size = 1) +

stat_summary(fun = mean, geom = "point", shape = 23, size = 3,

fill = "red", color = "darkred") +

labs(

title = "Penguin Body Mass Distribution by Species",

subtitle = "Red diamonds show means, boxes show quartiles and outliers",

x = "Species",

y = "Body Mass (grams)",

fill = "Species"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position = "none")

```

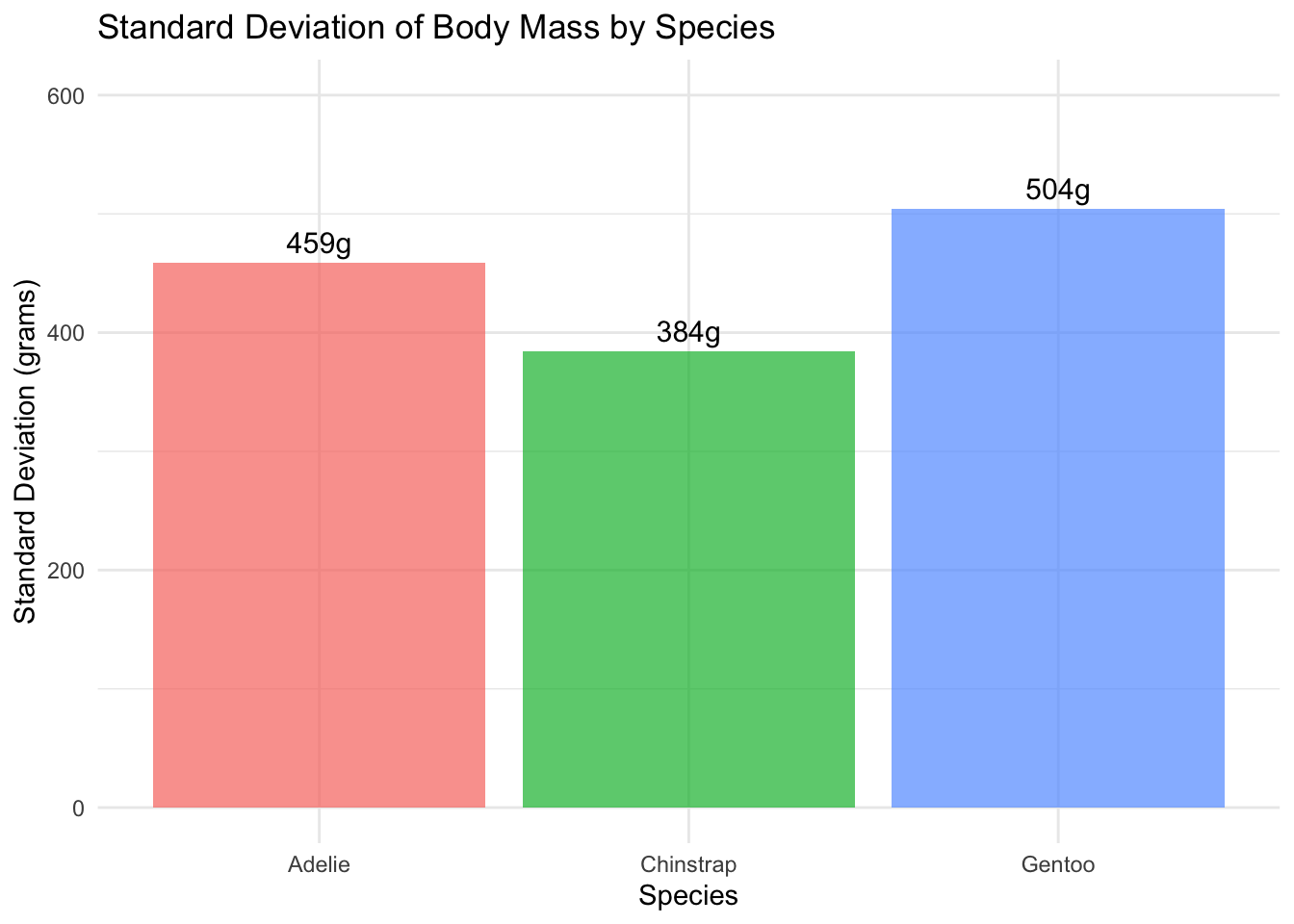

```{r}

#| label: fig-sd-barplot

#| fig-cap: "Standard Deviation of Body Mass by Species"

# Create a second plot showing standard deviations

species_stats %>%

ggplot(aes(x = species, y = std_dev, fill = species)) +

geom_col(alpha = 0.7) +

geom_text(aes(label = paste0(round(std_dev, 0), "g")),

vjust = -0.5, size = 4) +

labs(

title = "Standard Deviation of Body Mass by Species",

x = "Species",

y = "Standard Deviation (grams)",

fill = "Species"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position = "none") +

ylim(0, 600)

```

These plots show that while Gentoo penguins have the largest absolute standard deviation, they also have the largest mean, so their relative variability is actually the smallest. The boxplot reveals that Gentoo penguins form a distinct group, contributing to the high overall variability.

## 6. Assumptions & Limitations

**When NOT to use standard deviation and variance:**

1. **With ordinal or categorical data**: These measures require numerical data with meaningful distances between values

```r

# Don't do this:

# var(penguins$species) # This would be meaningless

```

2. **With highly skewed data**: Standard deviation can be misleading

```r

# Example of skewed data

skewed_data <- c(1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 100)

mean(skewed_data) # 13.6

sd(skewed_data) # 32.3 - larger than the mean!

# Consider median and IQR instead

median(skewed_data) # 3

IQR(skewed_data) # 2

```

3. **When outliers are present**: Both measures are sensitive to extreme values

```r

# Robust alternatives for outlier-prone data

mad(penguins_clean$body_mass_g) # Median Absolute Deviation

```

```

[1] 742.3

```

**What to do instead:**

- Use median and interquartile range (IQR) for skewed data

- Use robust measures like MAD for outlier-prone data

- Consider transforming data (log, square root) for highly skewed distributions

## 7. Common Mistakes

**1. Confusing population vs. sample formulas:**

```r

# R uses sample formulas by default (dividing by n-1)

# This is usually what you want

var(c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)) # Correct for sample data

# Manual calculation showing the difference:

x <- c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

n <- length(x)

sample_var <- sum((x - mean(x))^2) / (n - 1) # Divide by n-1

pop_var <- sum((x - mean(x))^2) / n # Divide by n

c(sample_var, pop_var)

```

```

[1] 2.5 2.0

```

**2. Forgetting about missing values:**

```r

# This will return NA if any values are missing

var(penguins$body_mass_g)

# Always handle missing data explicitly

var(penguins$body_mass_g, na.rm = TRUE) # Correct approach

```

```

[1] NA

[1] 644988.4

```

**3. Misinterpreting units:**

```r

# Variance is in squared units - harder to interpret

var(penguins_clean$body_mass_g) # 644988.4 grams²

# Standard deviation is in original units - more intuitive

sd(penguins_clean$body_mass_g) # 803.1 grams

```

## 8. Related Concepts

**What to learn next:**

1. **Coefficient of Variation**: For comparing variability between datasets with different means

```r

cv <- function(x) sd(x, na.rm = TRUE) / mean(x, na.rm = TRUE) * 100

cv(penguins_clean$body_mass_g) # 19.1% variation

```

2. **Standardized scores (Z-scores)**: Converting values to standard deviations from the mean

```r

penguins_clean %>%

mutate(z_score = scale(body_mass_g)[,1]) %>%

select(body_mass_g, z_score) %>%

head()

```

3. **Confidence intervals**: Use standard deviation to estimate population parameters

**Alternative measures when standard deviation isn't appropriate:**

- **Interquartile Range (IQR)**: `IQR(x)` for skewed data

- **Median Absolute Deviation (MAD)**: `mad(x)` for robust measure

- **Range**: `max(x) - min(x)` for simple spread measure

Understanding variance and standard deviation opens the door to hypothesis testing, regression analysis, and quality control methods - making them essential tools in any data analyst's toolkit.